You are using an outdated browser that is no longer suitable for modern web standards.

Please update (or change) your browser to view our site as it is intended to be seen. Thank you.

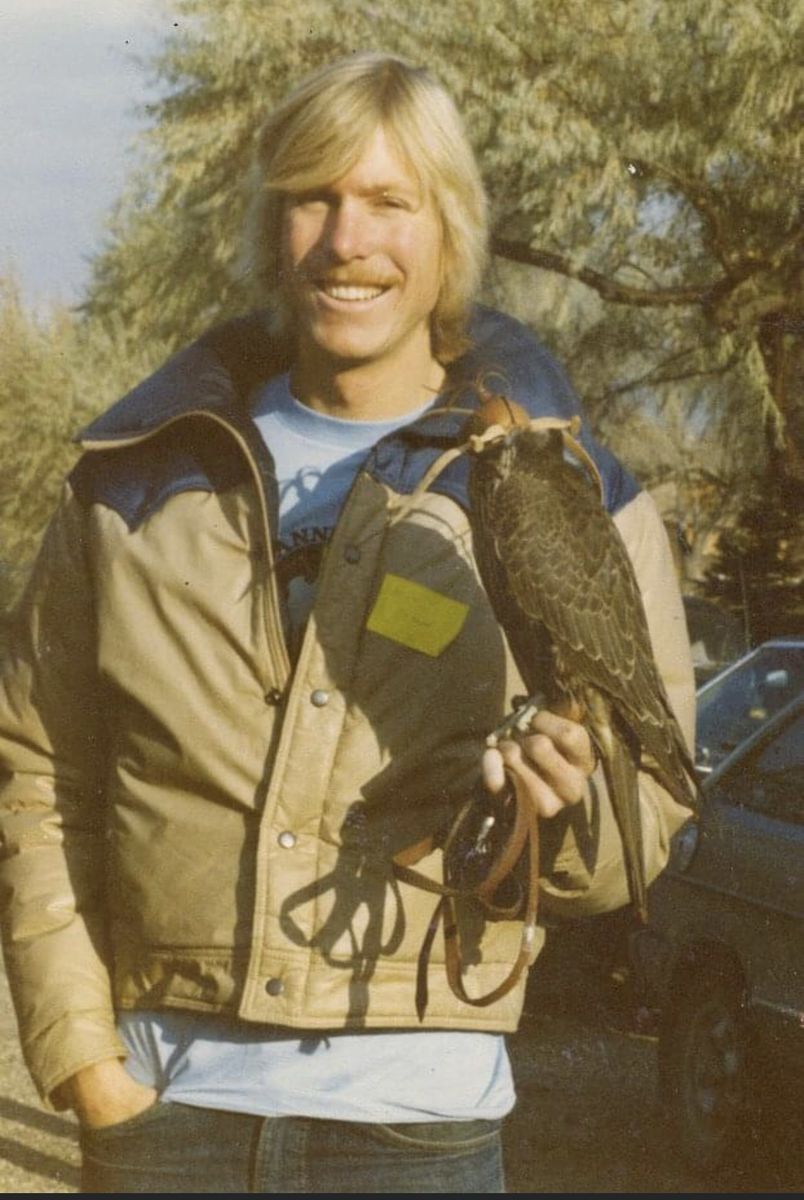

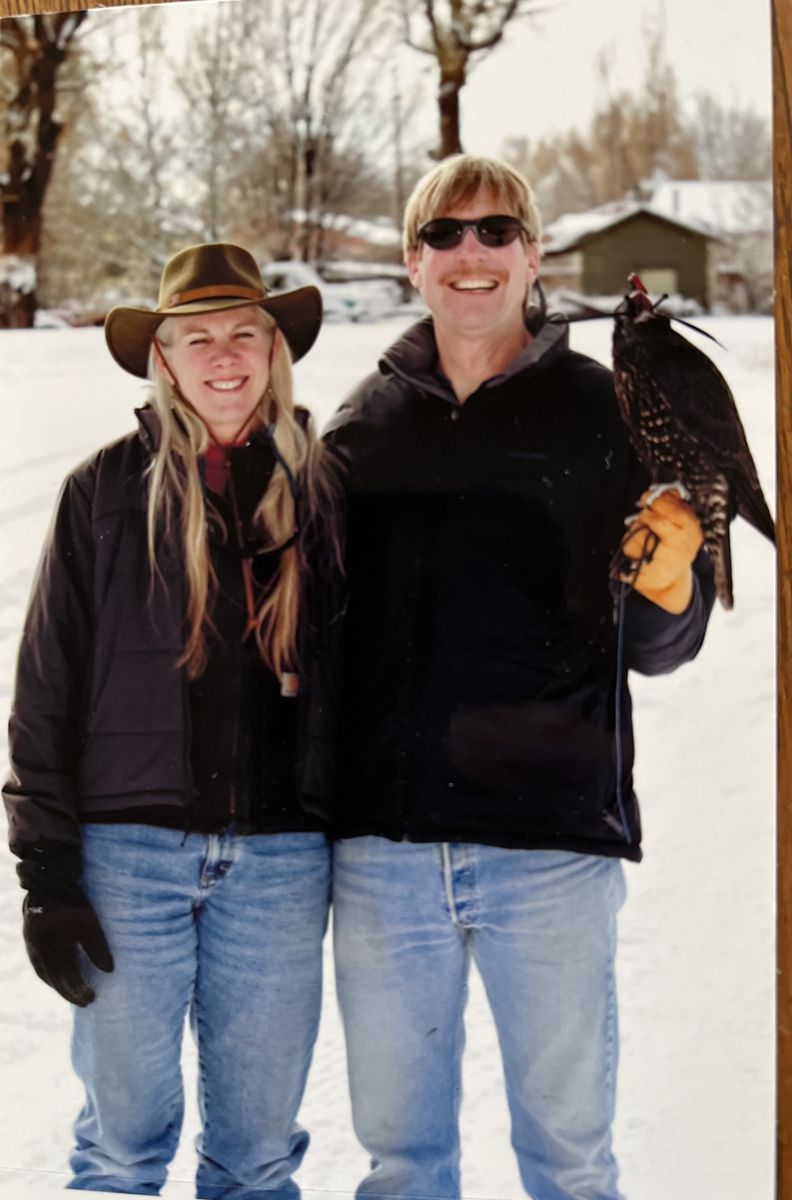

Rick Sharpe

4/5/1955 - 5/8/2022

American falconry lost one of its most skillful practitioners when Rick Sharpe passed away unexpectedly on May 8, 2022, at his home in Sheridan, Wyoming. He left behind the love of his life, his wife Gwen. The suddenness of his departure neither diminished the fullness of the life he lived nor the contributions he made to the art of falconry and the science of raptor conservation.

Rick grew up in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, where he first developed his lifelong fascination with nature, particularly birds of prey. As a young man, he spent his free time hiking through the hills, scaling cliffs, and climbing trees to learn more about local raptors. He was fortunate to have grown up in a family that nourished his love of nature and allowed some of these strange creatures that he collected to set up residence in the Sharpe home. Channeling this fascination into his educational pursuits, Rick chose to major in biology at Chico State University, where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree. While in college, Rick also cemented his lifelong obsession by becoming a licensed falconer.

Upon graduation, Rick synthesized his educational training with his love for raptors by joining the staff at the University of California Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group. He was among a group of young, visionary researchers who helped steer the critically endangered peregrine falcon from the brink of extinction. Rick and his colleagues hardly fit the stereotype of distinguished laboratory-bound scientists, but the results of their efforts led to one of the most amazing animal recoveries of the past century.

After leaving Santa Cruz, Rick channeled his gift for training birds into employment as a professional bird handler at avian shows in Fresno, CA and Minneapolis, MN. As he did while working at UC Santa Cruz, Rick found time to hone his bird training skills on his favorite birds - falcons. He, again, combined his research knowledge with his bird training skills, developing a capacity for training falcons that few could rival. When it came to flying his birds, he was never in a hurry. His meticulous eye for detail and his regimented routines for flying could sometimes present a challenge to his less-patient friends, but the results of his efforts were obvious. He often mitigated this problem by flying at or past dusk, when no one else was waiting to fly.

As an avid falconer who adjusted his lifestyle to accommodate his passion, Rick spent much of his adult life hunting with his falcons across the western States. His travels allowed him to make friends not only in the US, but worldwide. They also added to his extensive collection of colorful stories. He had many opportunities to showcase his talent in sky trials across the western states. In these competitions, Rick was always among the favorites. His reputation, however, never affected his ego. While respected for his falconry skill and insights, he also made many friends by showing an honest willingness to help others. He was a member of North American Falconry Association, California Hawking Club, and the Wyoming Falconers’ Association. At NAFA Meets, Rick and Gwen entertained numerous friends by providing Thanksgiving dinner for those far from home. He enjoyed the community of local falconers, as well, after moving to Sheridan in 2003 and found camaraderie in sharing their singular passion.

As keen observers of nature, Rick and Gwen shared a love of wildlife. Gentle and caring souls, they treated their own animals like royalty, while rescuing and rehabbing many others when the situation arose. In addition, Rick was known as an avid storyteller. At any social gathering, he could be found regaling others with his tales. Many of these stories were documented by the VHS tapes that he recorded during his adventures. He had started to digitize them in the last few years, sharing memories from clips with falconry friends across the States and abroad. Homeschoolers in Sheridan enjoyed his falconry presentations as did the Boy Scouts and Senior Citizens in Ashland, Kansas, where his falcons hunted prairie chickens for over 30 years. Those who were lucky enough to count Rick among their friends will have fond memories and at least a few interesting “Rick Sharpe stories.” Rest in peace, Rick. We miss you.

Tribute written by Bill Murphy.

I met Rick in the early 1980s and sparked a friendship built on the fact that we were both in our early 20’s, completely crazy about falconry, and wanting to get better at it. Rick was further along in experience as a longwinger, so I absorbed all I could through conversation and watching him fly his eyass prairie falcon. My strongest impressions from those early days were Rick’s attention to detail in the daily management of his bird and the emphasis he placed on establishing a positive routine for hunting success.

For years after, Rick would randomly stop by our home and stay for a few days or a week’s hawking during the fall or winter, and I was consistently impressed by how well his falcons flew. His focus on detail and routine were ever present, and both were continually refined by greater time and experience in the art. As anyone who knew Rick can tell you, his focus and dedication allowed him to achieve an exceptional level of success as a falconer.

As Rick’s friend, I can also attest that his fixation on detail and routine had a few comedic moments. One such memory came from a visit in late December, sometime in the early 2000’s. John Goodell lived in the valley then, and we were mostly hawking ring-necked pheasants in CRP grass on the benchlands. The hunting was good; heavy snow had not yet settled on the valley so access was reasonable, and pheasant numbers were way up. I had two English setters, Max and Skye. Max was the older, and very reliable dog, and Skye was, well, not reliable. At all. She had just begun to hold point that fall and could claim fewer than a half-dozen steady points on wild birds in her lifetime.

Hub Quade was also visiting when Rick arrived, and we caravanned out for a morning of fun. Rick followed in his own truck, but had said his hybrid gyr/peregrine’s weight was high and would likely not be ready to hunt until later that day. Within a couple of hours, we had flown several falcons over Max and since the hawking was done, I decided to try to give Skye more experience on wild birds. Well, a few minutes into the field, she struck a solid point. I don’t remember if I asked Rick if he wanted to reconsider, or if he asked me not to flush while he thought about flying the point, but the outcome was that we held our breath while Rick carefully discussed his bird’s readiness to hunt with the group of us, before deciding to walk back to his truck and weigh it again before finalizing his decision. I clearly remember telling him that Skye could not be counted on to wait, as I secretly sweated with anxiety, but Skye stayed fixed in her pose.

After what seemed like an hour, Rick made his way back into the field with his falcon on the glove. We spent another minute or two discussing whether I thought the point was still good, how the flush might go, and where the (presumed) pheasant would seek cover. Since it was likely a pheasant point, in a large expanse of CRP grass, there was really no way to know if the bird was even still in the same zip code. Hub said “no fear Rick”, and he decided to give it a go. I felt relieved -and more than a little astonished- to see Skye still holding point when Rick slipped the hood and his hybrid bolted into the air. Rick’s falcon flew well, as usual, and took the hen pheasant we flushed from Skye’s point in fine style. Great morning with good friends!

– Jeff Broadbent

I met Rick in the late 90’s in the first few years of my falconry experience as I began flying my first longwing. Rick would come through my mountain valley a couple times each season on his way to and from hawking chickens in epic destinations that I could only imagine. While we didn’t have prairie chickens, we did have pheasants that could be found in classic set-ups; a wide-open canvas of snow punctuated by small island refugia hundreds of yards away. I was flying an aggressive female peregrine who often exhibited a relatively poor pitch, while Rick’s hybrids would, of course, put on a master class in pitch and position. I was striving to realize more of my falcon’s potential and this unassuming, soft-spoken visitor to our valley was a formative influence.

What struck me immediately was the incredible discipline with which he approached falconry; his bird’s conditioning, careful feeding regimes, exacting weight control, and unbending commitment to their stylish performance in the air. I soaked up everything he offered, from feeding his birds rinsed meals in a bowl of water on their off-days, to his ballooning or kiting rigs, perch designs, and his self-control during a flight. Rick’s will power pushed his tiercel’s style up and up.

In retrospect, I realize now that his gentle, warm manner combined with his intense commitment to exceptional falconry was a truly rare quality.

– John M. Goodell

Donations for Rick Sharpe’s plaque made by: Bill Murphy, Mike and Karen Yates, Sheldon Nicolle, Edward Sharpe, and Steven Bachel